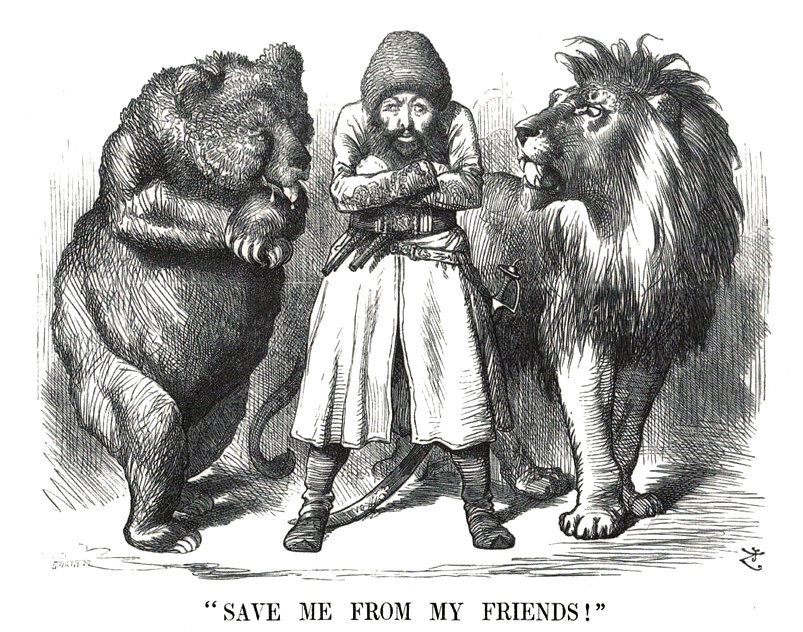

(Political cartoon depicting the Afghan Emir Sher Ali with his "friends" the Russian Bear and British Lion, 1878)

The 19th Century conflict that became known as the Great Game, occurred within the wider context of the battle between world powers for trade and political influence in Central Asia. The main players were the Russian and British Empires, and to a lesser extent, France and Iran. India, Britain’s ‘Jewel in the Crown’ featured as a prize and the Khans and Emirs of Central Asia became the pawns, while their homelands were the board upon which the big players made their moves.

There is no general consensus as to the exact dates for the beginning or end of the ‘Game’. January 1830, when the Governor General of India was asked to establish a trade route between India and Bukhara, is sometimes cited as the start. However, it could also be argued that Napoleon’s intentions to join with Russia in an overland invasion of India, at the beginning of the century, marked an early phase of the ‘Game’.

An immediate problem that faced all foreign powers was the fact that little was known of the topography of the region, the location of rivers and the accessibility of mountain passes. The same could be said for its inhabitants, the complexity of the tribal system, the number and size of the towns and villages and the strength of their defence forces, both in terms of fortifications and manpower.

The British particularly needed to know how viable it would be for initially the French, and later the Russians, to invade India from an overland route. On the other hand, Russia was concerned that the presence of the British in the region threatened her expansionist policies in Central Asia.

During the early decades of the 19th Century, both Russia and Britain commissioned map-makers and spies to gather intelligence on the topography and the people. They were fluent in the local languages and usually disguised themselves as traders. Their hazardous journeys often lasted up to six years and risked death from starvation or the cold. Those who did not die from the rigours of the journey, often suffered a gruesome death at the hands of tribesmen. Those who did return brought back valuable information, some of which was later published.

Throughout the period of the Great Game, Afghanistan was ruled by two major Pashtun tribes; the Sadozai, also known as the Durrani, and the Barakzai. Ahmad Shah Durrani, the founder of modern Afghanistan, attempted to unite all the tribes that straddled today’s Afghanistan and Pakistan. However, when Zaman Shah Durrani, who came to the throne in 1793, murdered many of the Barakzai leaders, he set in motion a tribal conflict that continued for decades, perhaps even until today.

Britain first became overtly involved in Afghan tribal politics in 1809, when Shah Shuja Durrani allied with the British East India Company. This move was not popular with the majority of the Afghans and when he was overthrown by Dost Mohammad Khan of the Barakzai Khan, Shah Shuja lived in exile in India at the expense of the East India Company. Twenty years later, with the help of the British, he returned to Afghanistan. Britain wanted a ‘friendly’ ruler on the throne, which meant ousting Dost Mohammad. It was a clear act of ‘regime-change’ and led indirectly to the First Anglo-Afghan War.

The Treaty of Gandamak (1879), that was signed during the Second Anglo-Afghan War, resulted in further British involvement in Afghanistan. Apart from losing considerable territory along her eastern border, the Afghans forfeited all control of her foreign affairs. Another damaging event was the establishment of the Durand Line that was agreed by the Afghan Emir, Abdur Rahman Khan. The aim was to agree a border between British India (now Pakistan) and Afghanistan, in the hope that this would improve diplomatic and trade relations. But because the line cut through Pashtun and Baloch tribal lands, it has never been officially recognised by many Afghan tribes. Consequently, ethnic Pashtuns and Balochis have always felt free to cross between Afghanistan and Pakistan, a situation that in recent years has enabled the Taliban to thrive.

The conflict along the northern border of Afghanistan between Britain and Russia, was finally settled with the signing of the Pamir Boundary Commission protocols in 1895. While this date marks the end of the Great Game, it did not resolve the conflict between Afghanistan and her more powerful neighbours. In many ways, the British and Russian involvement in the country in the 19th Century, simply laid the ground for an even more turbulent 20th Century.

Russia's influence in the region continued throughout the Soviet period, while British influence declined after Indian Independence. Two-day China is a main player while Central Asian countries such as Uzbekistan are now enjoying a new sense of independence. But Afghanistan remains a turbulent and unstable country, a situation that is perhaps not helped by the continued presence of foreign troops.

We have to ask, 'Was anything learned from the Great Game of the 19th Century, or is history repeating itself, albeit with different players within a different context?

(For a more detailed article, see The Great Game)

Extracts from A History of Central Asia

*****

Comments