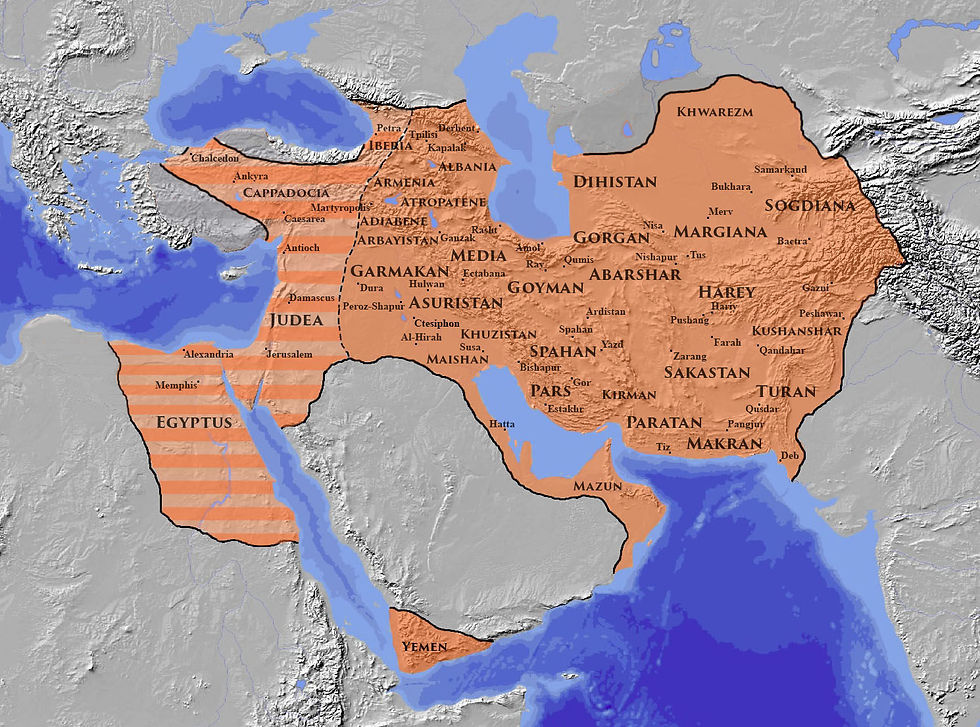

The Sassanid Empire, (224-651 CE) also known as the Empire of the Iranians, or the Neo-Persian Empire was the last Persian power to exist before the arrival of Islam. At its greatest extent, in around 620 CE the Sassanids ruled a vast area that stretched from Egypt in the West to Pakistan in the East, including parts of Arabia, the Caucasus and virtually the whole of Central Asia.

The Empire was named after Sassan, who was the grandfather of Ardashir I, the founder of the Empire. Ardashir was born in Fars, also known as Pars or Persis, which is thederivation of the name Persia.

Coming from Fars, the Sassanians viewed themselves as being truly Persian and therefore the rightful descendants of the ancient Persian Achaemenids. The Seleucids and Parthians, on the other hand, had been strongly influenced by the alien culture of Hellenism. Consequently, throughout their reign, the Sassanids aimed to reduce Greek and Hellenistic influence in favour of Persian culture. Central to this policy was the promotion of Zoroastrianism, although throughout most of the Sassanian period, other religions, especially Judaism and Christianity, were tolerated.

Ardashir I: 224-242 CE

There are various sources, with differing accounts, as to how Ardashir, also known as ‘the Unifier’, came to power. The general consensus is that his, grandfather, Sassan, was warden of the Zoroastrian temple at Istakhr, three miles from the ancient city of Persepolis. Many of the stones used to build the temple had been taken from the ruins of Persepolis that was previously sacked by Alexander the Great. (See Chapter 3) For a short time, Istakhr was the capital city of the Sassanids and it remained an important centre for Zoroastrianism for many centuries and well into the Islamic period.

Papak, Ardashir’s father, was both a grand priest of the temple and the king of Pars, which was a vassal state of Parthia. When Papak died in 222, Ardashir seized the throne of Pars from his brothers and assumed the title King Ardashir V of Pars. He then went on campaign conquering the western parts of Parthian territory. After several minor battles, Artabanus IV, the Parthian King of Kings, finally decided to confront him.

On 28th April, 224, a battle took place between Ardashir and Artabanus, possibly at Ramhormoz in the Khuzestan Province of today’s Iran. Ardashir was accompanied by his son and successor, Shapur, together with around 10,000 Cavalry wearing Roman-style flexible chainmail. Although the Parthian troops were greater in number, they were at a disadvantage due to their heavier, leather armour, which was typical of the Parthian military. Artabanus, the last King of Kings of the Parthian Empire was killed in battle. So, ended the long line of Arsacid rulers, while Ardashir became the founder and first King of Kings of the House of Sassan. He was crowned Shahanshah at the ancient city of Ctestiphon, while his wife was crowned Adhur-Anahid (Queen of Queens). He established his capital city at Gur, today’s Firuzabad, where remains of his palace can still be seen today.

Ardashir believed that he was destined to rule by divine right. He self-identified with the semi-mythical Kayanian dynasty, whose heroes feature in the Avesta, the sacred text of Zoroastrianism. In about 235, he commissioned work on a rock relief depicting his investiture. The location of the relief is at Naqsh-e Rostam, the necropolis of the Achaemenids, which was near Persepolis. The work, which can still be seen, shows Ahura Mazda, the highest deity of Zoroastrianism, handing Ardashir the ring of kingship. Both men are on horseback. Artabanus, the last Parthian king is shown being trampled beneath the hooves of Ardashir’s horse, while the Ahriman (the devil) is trampled beneath the horse of Ahura Mazda. The inscription, written in Middle Persian, Parthian and Greek, reads: "This is the figure of Mazdaworshiper, the lord Ardashir, Shahanshah of Iran, whose lineage is from Gods, the son of the lord Papak, the king". Clearly Ardashir’s motive for commissioning the work was to legitimise his overthrow of the Parthians and his subsequent rule of ‘Iran’, by divine right. The inscription bears the first known reference to ‘Iran’. While initially the name ‘Iran’ appeared in a religious context, in time the word came to describe a geographical region.

After conquering Parthian territory in the West, Ardashir gained the submission of Turkmenistan, Chorasmia (modern Khwarezm) and Balk in Afghanistan. He then annexed Mosul in today’s Iraq and also Bahrain in the Persian Gulf.

Shapur I: 240-270 CE

According to the sources, Ardashir named Shapur as his successor on the grounds that he was “the gentlest, wisest, bravest and ablest of all his children”. (Shapur Shahbazi, ‘SAPUR I:History Encyclopaedia Iranica), Certainly, Shapur had probably proven his military ability during the battle against Artabanus, when father and son fought side by side. Also, since accounts of the time refer to ‘two kings’, it is thought that Ardashir and Shapur shared the crown for approximately a year before Ardashir died.

Throughout the four hundred years of Sassanid rule, the Empire was constantly at war with Rome, as each power fought for control over the Eastern Mediterranean and Iranian plateau. There were two major campaigns during the reign of Shapur. The first came in 242-4, when the Sassanids captured the city of Hatra. During the battle, the young Roman Emperor Gordianus III was killed and Philip the Arab was proclaimed Emperor. Roman sources record that Philip made a shameful peace treaty with Shapur and ceded Armenia to the Sassanids, along with the payment of 500,000 dinars as ransom for his life.

The best-known of Shapur’s campaigns was in around 260, when the Roman Emperor Valerian, and his senior troops, were captured at Edessa and sent as prisoners to Pars. Valerian spent the rest of his life in captivity and Shapur marked the event with another rock-face relief at Naqsh-e-Rustam. The capture of the Roman Emperor has also been portrayed in other art forms down the centuries, for example, Hans Holbein the Younger’s 1571 sketch entitled ‘The Humiliation of Valerian”. At the time, many Christians believed Valerian’s downfall to be punishment for his persecution of Christians under Roman rule.

As the Sassanids made inroads into Roman-held Mesopotamia and Syria, they acquired wealthy cities and valuable manpower. Those captives who had previously worked on Roman roads, viaducts and bridges, were particularly prized. Shapur and his successors employed them across the Sassanid empire in the construction of dams, bridges and new cities such as Bishapur, in today’s Pars Province and Nishapur in northeast of Iran.

Religious Policy

Shapur I, like his father, promoted Zoroastrianism. He founded new fire altars and temples and raised the status of Zoroastrian priests, who accompanied troops on campaign. At the same time, he was tolerant towards other religions. Among the captives who were relocated from Syria to other parts of Shapur’s Empire, were many Christians who discovered that life under the Sassanids offered a religious freedom unknown under the Romans. Under Shapur, they were able to build their own churches, monasteries and establish bishoprics.

Shapur I also had a good relationship with the Jewish community. For example, Rabbi Samuel, who was head of the Yeshiva at Nehardea in Babylonia, encouraged the Jews to be loyal to the victorious Persians. It is said that Samuel was looking towards the Messianic Era and he possibly believed that Shapur I would be instrumental in restoring the 3rdTemple at Jerusalem, just as his predecessor, Cyrus the Great, had helped restore the 2nd Temple.

Apart from the presence of Christians and Jews, Manicheans were growing in number. Named after their founder, Mani, Manicheans were influenced by Gnosticism. Gnostics believed in a dualistic cosmology whereby all things material, including the body, were bad and had been created by a lesser god, while the pure realm of the spirit, is the creation of the supreme, unknowable God.

The founder of the religion, Prophet Mani, was born in 216 in the Parthian vassal state of Seleucia-Ctesiphon. His father was a member of a Jewish/Christian sect of the Elcesaites, which was a branch of the Gnostic Ebionites. When Mani was just 12, and again at 14, he received visions from his ‘spiritual twin’, telling him that he should leave his home and travel to India. While in India, he learned about Hinduism, elements of which he then incorporated into his own Manicheaistic thought. The doctrine of reincarnation is one example and he came to believe that he was the reincarnation of Zoroaster, the Buddha and Jesus.

Mani wrote six major works in Syriac and another, the Shabuhragan, was written in Middle Persian and specifically dedicated to Shapur I. During the reign of Shapur I and the brief reign of his son, Hormizd I, Manicheanism flourished and Mani was a frequent visitor to the royal court. However, when Bahram II came to the throne in 274, everything changed. He was a staunch supporter of Zoroastrianism and under pressure from the priests he began a systematic persecution of Mani and his followers. In 274 Mani was imprisoned and died within a month. Some accounts claim that he was flayed alive, and his skin stuffed with straw. The grim effigy was then hung over the main gate of the city of Gundeshapur as a warning to his followers, many of whom fled to India and China.

Generally speaking, Christians fared well under the Sassanids until Constantine the Great became Roman Emperor in 307. Under Constantine, two Edicts were passed: the Edict of Toleration (311), ending Diocletian’s persecution of Christians, and the Edict of Milan (313), legalising Christianity across the Roman Empire. These Edicts changed the status of Christians, who became much more powerful throughout the Roman Empire. However, the Romans were long-term enemies of the Persians and the Sassanids feared that Christians in the Persian Empire might collaborate with Roman Christians, a situation that could threaten the security of the Sassanids. Consequently, Bahram II endeavoured to persuade his Christian elite to convert to Zoroastrianism. At the same time, all religious minorities faced increased discrimination.

Khosrau I: 531-579

One of the greatest of the Kings of Kings was Khosrau I, also known as the ‘philosopher King’ or ‘ideal King’. He is best known for his major reforms as well as his patronage of the arts, sciences and philosophy, much of which was later inherited by Islam.

A significant change under Khosrau was the introduction of a new social class of small landowners (deghans).Previously, society was broadly divided into three groups: the priests, the nobility and the peasants. Functioning as a feudal society, the landowning nobility had ruled with considerable autonomy and held great power. They had maintained their own armies and raised their own taxes. Khosrau reformed the military system whereby the small landowners became the backbone of a new centralised army, rather than the previous system whereby the army was raised by feudal levy.

At the same time, Khosrau reformed the taxation system. Previously, the nobility was exempt from paying taxes. Under the new scheme, all landowners, large and small, were liable to taxation. Rates were set according to the amount and type of yield produced, e.g. date palms, olives, etc. Furthermore, all taxes were to be submitted directly to the central government rather than through ‘middle-men’, or tax-gatherers as previously. Another important element of Khosrau’s centralisation policy was a reduction in the number of satrapies in favour of the establishment of four distinct provinces, with each province having its own garrison town and ‘royal city’.

Decline of the Sassanids

In around 453, Yazdegerd II (435-457) was forced to move to the east in order to deal with invading Hephthalites, or White Huns, who had settled in Bactria. For the next hundred years or so, the Hephthalites and Sassanids were at times allies, at other times enemies. By 600, the Hephthalites were strong enough to invade Sassanid territory as far as Spahan (today’s Isfahan Province). They finally submitted to the invading Arab Muslims in 705. (See Chapter Six)

Between 602 and 628, the Sassanids were at constant war with the Roman Byzantine Empire as each power fought for control over the Levant, Egypt, the Eastern Mediterranean and Asia Minor. In 614, Khosrau II (590-628) conquered Jerusalem and seized the True Cross, traditionally believed by Christians to be the remains of the cross on which Jesus was crucified.

With ongoing war in the East against the Hephthalites, and wars in the West with the Byzantines, the Sassanids were virtually bankrupt, both militarily and financially. The burden fell on the people, who were unable to pay higher taxes to pay for the wars, while at the same time livelihoods were lost due to social and economic breakdown.

The Byzantines took advantage of this situation and in 622, Heraclius, the Byzantine Emperor, launched a counter-offensive. Over the next five years, the two powers waged war, at huge human cost and the desecration of the most important fire temples. When peace was finally restored in 627, the Byzantines regained lost territory. But above all, they retrieved the True Cross, which was taken ceremoniously back to Constantinople before finally returning it to Jerusalem.

Khosrau II was blamed for this humiliation in the face of the Byzantines and in 628, he was murdered on the orders of his son, Kavad II. During the following four years, chaos reigned and five different kings ruled. Civil war broke out and power fell to the Generals.

Yazdegerd III came to the throne in 632, at the age of eight. During his rule, Arabs, who followed the new religion of Islam, began to invade the Persian Empire. Yazdegerd spent most of his life trying to raise armies in order to repel the Arabs. When this failed he fled to Marw, in today’s Turkmenistan, where he was apparently murdered by a miller. According to tradition, he was buried by Christian monks. His son and heir sought refuge in China.

Yazdegerd III was the last in a long line of the King of Kings. His death marked the end of the Sassanid Empire, which was the last Persian Empire before the arrival of Islam in Asia Minor, Central Asia and beyond. But it was not the end of Persian culture, including art, architecture, literature and philosophy, which was to continue to influence the Muslim world to this day.

*****

Extract from A History of Central Asia

Comments