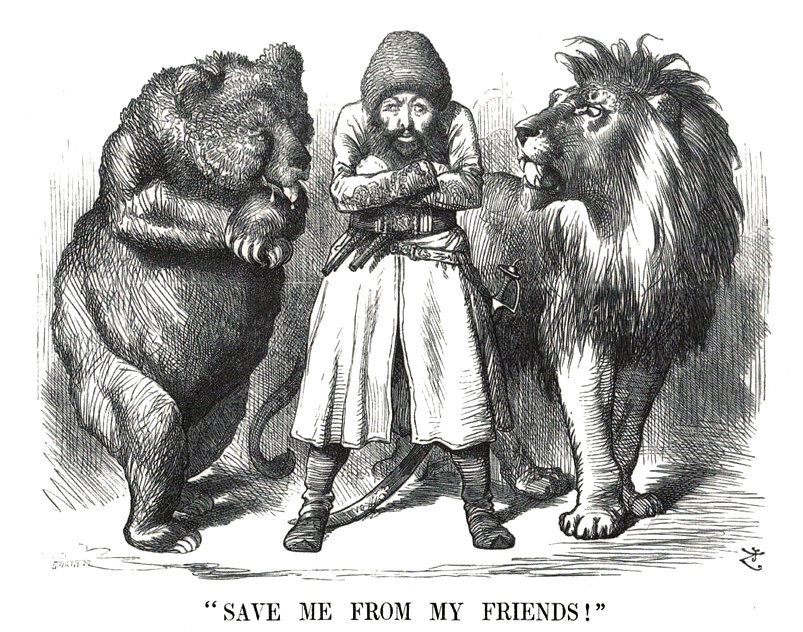

(Political cartoon depicting the Afghan Emir Sher Ali with his "friends" the Russian Bear and British Lion, 1878)

The Great Game: 1830-1895

The term, ‘the Great Game’, Le grand jeu, in French, can be traced back at least as far as the late 16th Century when it was associated with games of risk, such as cards and dice and those involving deception. It was first coined, in reference to the rivalry between Britain and Russia, in July 1840, by Captain Arthur Conolly. He was an Intelligence Officer with the British East India Company and was writing at the time to Major Henry Rawlinson, a British agent stationed at Kandahar. Conolly suggested to Rawlinson that he had ‘a great game and noble game’ ahead of him in the advancement of Afghanistan. Rudyard Kipling’s popular novel Kim, also brought the attention of the British people to the 19th Century rivalry between Britain and Russia. However, the term did not come into general usage until after the Second World War, and there is no general consensus over the exact date as to when the ‘Game’ began and when it finished.

Afghanistan was then, as now, strategically important, being at the crossroads between Central Asia, Russia, and the Indian subcontinent. During the 19th Century, the country was pivotal in the conflict between Russia and Britain, as each competed for influence in the region.

As early as 1717, Peter the Great had sent a delegation to the Khanate of Khiva offering Russian protection in exchange for trading rights to the rich mineral resources of the Oxus delta that he desperately needed to pay for his European wars. The Khan rejected the offer and massacred most of the Russian delegation. However, as part of Russia’s eastwards expansion, Cossacks continued to make inroads into Central Asia. Russia also believed that the British presence in the region posed a direct threat to her own trade ambitions. Britain, on the other hand, suspected that Russia’s ultimate aim was to gain access to India, Britain’s ‘Jewel in the Imperial Crown’.

At the beginning of the 19th Century, the French also had territorial ambitions in British India. Napoleon’s initial plan had been to launch an invasion from Egypt, but his navy was virtually destroyed in 1798 by Horatio Nelson at the Battle of the Nile. Consequently, he was forced to consider an overland route and he discussed a joint Russian/French invasion with Emperor Paul I of Russia. Nothing materialised, however. First, because Russo/French relations deteriorated under Paul’s successor, Alexander I, and second, the French threat declined following Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Borodino in 1812.

The defence of India was hotly debated in the British Parliament. Opinion was divided between the Russophobes, who called for an aggressive ‘Forward Policy’, and those who recommended a ‘Backward’, or inactive policy. Those who recommended the ‘Forward Policy, believed that the best strategy was to gain the loyalty of the Central Asian Khanates ahead of the Russians. The strategy was to make Afghanistan a protectorate and use the Ottoman and Persian Empires, as well as the Khanates of Khiva and Bukhara, as buffer states against Russia. The more cautious advocates of an inactive policy, doubted the seriousness of the Russian threat, largely on the grounds that any invading army from the north would face the challenge of an unknown and inhospitable terrain that was inhabited by dangerous warlike tribes.

The early explorers

Britain and France were sea powers and therefore, for them, control of sea the routes had been paramount for centuries. But with the onset of the Great Game, the focus in the region changed to overland routes from Persia and Russia to India. However, knowledge of the Central Asian terrain was extremely limited, and in some cases based on little more than the campaigns of Alexander the Great centuries earlier. (See Chapter 3) Consequently, the British employed Indian hill men, disguised as Hindu or Muslim holy men, as guides and often as spies, while the Russians used Mongol tribesmen disguised as Buddhist monks. But the primary task of mapping the region and intelligence gathering on both sides was undertaken by Europeans.

In 1810, Lieutenant Henry Pottinger and Captain Charles Christie, both officers with the British East India Company, were commissioned to map the route from Nushki in Pakistan to Isfahan in Central Iran. The purpose was to assess the viability of a Russian or French overland invasion of India.

Disguised as Muslim horse dealers, the two men took different routes. Pottinger travelled 900 miles westwards across the Central Asian deserts. During the difficult journey, he described his throat as being ‘so parched and dry that you respire with difficulty, to dread moving your tongue in your mouth from the apprehensions of suffocating…’. (Peter Hopkirk, The Great Game, On Secret Service in High Asia)

Christie first travelled north to Herat, a city renowned for its horses. He then journeyed on to Isfahan, where the two men were reunited on the 10th June 1810. Their journeys had taken over three months. Christie had ridden 2,250 miles and Pottinger over 2,400 miles. Throughout their travels, the two men gathered intelligence concerning the tribes, their leaders and numbers of fighting men, as well as the location of wells, rivers, crops and vegetation, all information that would prove invaluable in the future.

Ten years later, in 1820, William Moorcroft led an expedition to Bukhara. Trained as a vet, Moorcroft first travelled to India in 1808, to take up the position of Superintendent of the Stud for the East India Company. Ostensibly, the purpose of the journey to Bukhara was to buy the famous pale golden Turkoman horses, known for their speed and stamina, and much talked about in the bazaars of Northern India. Although his expedition was financed by the East India Company, Moorcroft had no official status and could not rely on British help if he got into difficulties.

Moorcroft departed from India on the 16th March 1820. He was accompanied by George Trebeck, a young Englishman and George Guthrie, an Anglo-Indian. Their caravan totalled 300 persons, including a number of Gurkhas as well as some of the finest British goods which Moorcroft hoped to trade with the Khanates. As a staunch Russophobe, Moorcroft was a firm believer in the Forward Policy and he thought that Britain should be ahead of the Russians in establishing good relations, initially through trade, with the Khanates.

Because of a civil war raging in the area, the caravan was forced to by-pass Afghanistan, which would have been the most direct route to Bukhara. The safest route was via Leh, the capital of Ladakh, in Chinese Turkestan. It was while in Leh that Moorcroft discovered that the Russians were ahead of the game. A Russian by the name of Meghti Rafailov, had been trading in Chinese Turkestan for some time and Russian goods were to be found in the bazaars. But Tsar Alexander I had commissioned Rafailov to travel even further South into the Punjab and open diplomatic negotiations with the Sikh ruler, Ranjit Singh, who at the time was on friendly terms with the British.

Moorcroft’s warnings about Russia’s intentions were ignored by the officials of the East India Company and so he decided to take things into his own hands by negotiating a commercial treaty with the ruler of Ladakh in exchange for British protection. Unfortunately, Ladakh was within Ranjit Singh’s sphere of influence. Fearful of upsetting the Sikhs, the British repudiated the treaty and suspended Moorcroft’s salary.

Despite his problems, Moorcroft and his party continued on their journey, arriving in Kashmir in 1822 and Kabul in June 1824. While in Kabul, they became the first Europeans to visit the famous Buddhas of Bamiyan that were unfortunately destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.

In February 1825, Moorcroft reached Bukhara. He did not find the famed horses, and to his disappointment, he discovered that the Russians had reached Bukhara four years previously. Moorcroft and his two companions died of fever six months later while on their return journey to India. He had been travelling for almost six years, during which time he wrote almost 10,000 pages of manuscript which were later obtained by the Asiatic Society. The papers were eventually published as Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Punjab, in Ladakh and Kashnair, in Peshawur, Kabul, Kunduz and Bokhara, from 1819 to 1825.

Other intrepid explorers followed. In 1829, Lieutenant Arthur Connolly of the British East India Company, travelled from St Petersburg to India via Astrabad in northern Iran, where he was arrested on suspicion of being a Russian spy. He then marched with the Afghan army as far as Herat and finally reached British India in January 1831. His travels were published in 1834 as A Journey to the North of India through Russia, Persia and Afghanistan.

Captain Sir Alexander Burnes’ book, Travels to Bukhara, became an overnight best seller in the same year. Burnes, who was a first-cousin of the poet Robert Burns, joined the East India Company at the age of 16 and became proficient in Persian and Urdu. By 1831, the British Government had begun to take the Russian threat seriously and so Burnes was commissioned to make a survey of the route from Kabul to Bukhara, as well as collect intelligence on Afghan politics. His book tells the story of how he travelled in disguise, first sailing up the Indus River and then on to Lahore, where he presented gifts from King William IV to the Sikh Ruler, Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Founding of Afghanistan: 1747

Ahmad Shah Durrani, an ethnic Pashtun of the Sadozai tribe, is credited with founding the modern state of Afghanistan. Ahmad was born in Herat in 1722. His father was the Governor of Herat at a time when the region came under the rule of Nader, Shah of Iran. (see Chapter Nine) When the Shah was assassinated in 1747, the Afghan tribes chose Ahmad as their leader, marking the beginning of an Afghan entity that was independent of either the Persians or the Mughals. It is said that when Nadir Shah was assassinated, Ahmad removed the Koh-i-Noor diamond from the arm-band of the dead man, thus the famous gem passed from the Persians to the Afghans.

By gaining the loyalty of the tribes, Ahmad was able to unite a region that straddled today’s Afghanistan, Pakistan, north-eastern Iran and Turkmenistan. He was also able to wrest parts of north-west India from the Mughals. The Mughals had been in steady decline since the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707 and had lost territory to both the British East India Company and the powerful Hindu Maratha Empire. The Afghan incursion into north-west India brought it into conflict with the Marathas and a fierce battle took place between the two powers at the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761. The result was a decisive victory for the Afghans and an awakening for the British in India to the fact that the Afghans posed a serious threat on their western border.

Ahmad Shah Durrani died on the 16th October, 1772 in Kandahar. As the founder of modern Afghanistan, he is often referred to as ‘Ahmad Shah the Father’. Mountstuart Elphinstone, the Scottish statesman and historian, who spent time with the East India Company, wrote that ‘His military courage and activity are spoken of with admiration, both by his own subjects and the nations with whom he was engaged, either in wars or alliances. He seems to have been naturally disposed to mildness and clemency’.

Timur Shah Durrani, the eldest son of Ahmad, succeeded his father as Shah of the Durrani Empire and married the daughter of the Mughal Emperor Alamgir II. Consequently, he was influenced by Mughal/Persian culture and was never very popular with the Afghan tribes. In an attempt to remove himself from the quarrelsome Pashtun clans, he moved the capital from Kandahar to Kabul and made Peshawar his winter capital. Timur died in 1793 and left 24 sons. He was succeeded by his fifth son, Zaman Shah Durrani. However, two other sons, Mahmud Shah and Shah Shujah, also competed for the throne, a situation that eventually led to civil war.

Zaman acquired the throne in 1793 with the help of Payindah Khan, leader of the Barakzai tribe. A few years later, when the two men had an argument, Zaman reacted by executing not only Payinday Khan, but many of his tribal elders. By so doing, he not only set in motion a blood feud between the Sadozai and the Barakzai, the two most powerful of the Afghan tribes, but he also undid the balance of power between the tribes that Ahmad Shah had worked so hard to maintain.

In 1800, Zaman was captured, imprisoned and blinded on the instigation of his half-brother Mahmud Shah, who then held the throne until 1803. After spending some years imprisoned in Kabul, Zaman was then given refuge, first in Lahore by the Sikh leader Ranjit Singh and then by the British at the frontier city of Ludhiana, where he lived in relative comfort with a pension paid for by the East India Company.

In July, 1803, Shah Shujah Durrani ascended the throne as King of Afghanistan. One of his first tasks was to attempt to end the blood feud with the Barakzai tribe through a marriage alliance. However, he made a far more significant alliance with the British in 1809. As part of Britain’s strategy aimed at averting a French or Russian invasion, Mountstuart Elphinstone was commissioned to lead the first ever delegation to Afghanistan. His task was to persuade Shah Shujah to agree to block any foreign power from passing through Afghan territory en route for India. In exchange, the Shah was promised British protection from any foreign aggression against his territories at a time when the Persians, the Russians and the Sikhs all posed a potential threat to Afghanistan.

The alliance made in 1809 would be the first of many that ultimately undermined Afghan sovereignty. However, this first alliance proved to be ineffectual because almost immediately, Shah Shujah was ousted by his brother Mahmud Shah Durrani. After imprisonment in Kashmir, Shah Shujah then fell into the hands of the Sikhs and was imprisoned in Lahore. While in confinement, he was forced to give up the Koh-i-Noor diamond to Ranjit Singh. Thus, the valuable gem passed from the Afghans to the Sikhs.

In 1818, Shah Shujah managed to escape to British India where he lived a life of luxury in Ludhiana. For the next twenty years, he and his court in exile was funded by the East India Company. The British believed that Shujah could prove useful in the future. If he were reinstated as King of Afghanistan, he could be a valuable ally and supportive of British policy in the region. The fact that Shah Shujah spoke openly of his plans to retake his throne, reinforced British aspirations.

First Anglo-Afghan War: 1839-1842

During the years that Shah Shuja was in exile in India, the Sodozai (Durrani) dynasty fractured, while the Barakzai tribe grew in power. A watershed moment came when Dost Mohammad, the eleventh son of Sardar Payendah Khan, chief of the Barakzai tribe, claimed the title of Emir of Afghanistan in 1826.

Apart from having a personal grievance against the Durranis, who had executed his father in 1799, Dost Mohammad had also made enemies of the Sikhs, who had seized Peshawar, Afghanistan’s second capital city. In the hope of retaking Peshawar, Dost Mohammad approached the British, proposing joint Afghan/British military action to retake the city. However, although the British were keen to remain on friendly terms with the Afghans, they felt that this could not be at the expense of upsetting the Sikhs, with their formidable French-trained military, the Dal Khalsa. This was a dilemma that frequently confronted the British.

Having been rejected by the British, it was not surprising therefore, that the Afghans would turn to the Russians. British fears of Russia’s involvement were confirmed in December 1837 by Alexander Burnes. He happened to be present in Kabul, working as a British agent at the same time as the Russian envoy, Yan Vitkevitch. When Lord Auckland, Governor-General of India, heard of this, in January 1838, he wrote to the Afghan ruler:

“You must desist from all correspondence with Russia. You must never receive Agents from them, or have aught to do with them without our sanction. You must dismiss Captain Viktevitch with courtesy; you must surrender all claims to Peshawar”. (Macintyre Ben, The Man Who Would Be King, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux)

Fearing that Dost Mohammad would ally with the Russians, in November 1838, Lord Auckland ordered an invasion of Afghanistan with the aim of removing him from the throne and installing the ‘rightful’ claimant, Shah Shujah of the Durrani dynasty who was then living in India at the expense of the British. The fact that Shah Shujah had been deposed around thirty years previously, that he was hardly known by the majority of Afghans and was extremely unpopular among those who did remember him, was seen to be irrelevant.

In December 1838, a joint Sikh/British army of 21,000 troops, plus some 38,000 camp followers, set off from the Punjab. 30,000 camels were needed to carry personal effects. One regiment took a pack of foxes for hunting and up to 40 servants accompanied each officer. The size and make-up of the train would indicate that this was not simply a small army escorting the return of a rightful King, but that the British intended to remain in Afghanistan for some length of time.

By the end of April 1839, British troops had taken Kandahar unopposed and in July they captured the fortress of Ghazni. In the face of the British advance, Dost Mohammad’s fighters began to desert and he fled with a few loyal supporters first to Bukhara, and he later lived in exile in India. By August, Shah Shujah had been reinstated as King of Afghanistan.

The British claimed that their presence in Kabul was necessary in order to ensure a smooth transition of rule from Dost Mohammad to Shah Shuja. They initially set up their headquarters in the Bala Hissar fortress and later moved to a cantonment which was away from the general population of the city. However, when foreign wives and children began to arrive, the Afghans suspected the British motive to be one of ‘occupation’.

Resentment towards the British presence grew when it became evident that foreign troops were having sexual relations with Afghan women. In such a conservative Islamic society, where honour killings were commonplace, conflict was inevitable. Even Alexander Burnes, who had been on extremely good relations with the Afghans, angered the people with his behaviour towards local women.

It was an incident in the home of Burnes, on the evening of the 1st November 1841, that proved to be the spark that lit the fire of rebellion. When it was discovered that he had not only given refuge to a runaway slave girl, but that he had slept with her, the Council of Pashtun Chiefs felt justified in declaring a Jihad against the British. The following morning, the people went on the rampage, looting shops and seeking revenge. In the havoc, Burnes was hacked to death.

After weeks of violent riots that resulted in many deaths on all sides, the Afghans agreed to the safe withdrawal of the British garrison. On the 6th January 1842, some 4,500 military and 12,000 camp followers, including British, Indian and a few Afghan women, began a long and hazardous journey, in the middle of winter, towards Jalalabad. Florentia Sale, (Lady Sale, wife of Colonel Robert Sale, describes the 80-mile struggle, through the snow-covered mountain passes, in her book, Lady Sale’s Afghanistan: an Indomitable Victorian Lady’s Account of the Retreat from Kabul During the First Afghan War.

Despite promises of safe passage, the convoy was attacked by Ghilzai tribesmen as it passed through the five-mile narrow gorge known as the Koord-Kabul Pass in the Hindu Kush. Of those who had not already frozen to death, most of the women and children were taken captive. The men were slaughtered in cold blood. Of the six soldiers who managed to escape on horseback, only one, Dr William Brydon, reached Jalalabad.

In April 1842, the British launched a punitive attack and retook Kabul. The city’s nobles were executed by hanging and the central bazaar was burned to the ground. Shah Shujah, who had been hiding in the Bala Hissar fortress, was assassinated by his own people. By September, most of the women and children were released from captivity, but a small number of women stayed behind as wives of local Afghans. Finally, the new Governor General, Lord Ellenborough, ordered the withdrawal of all British troops from Afghanistan and Dost Mohammad Khan returned from exile to take up his throne.

According to Martin Ewens, (Afghanistan: A short History of its People and Politics), Dost Mohammad is said to have remarked to the British:

I have been struck by the magnitude of your resources, your ships, your arsenals, but what I cannot understand is why the rulers of so vast and flourishing an empire should have gone across the Indus to deprive me of my poor and barren country.

Second Anglo-Afghan War: 1878-1880

By 1878, the Emir of Afghanistan was Sher Ali Khan, son of Dost Mohammad. The situation in India had also changed. Following the Indian Uprising in 1857, rule in British India had been transferred from the East India Company to a Viceroy and Governor General who was directly responsible to the British Crown in London. At the same time, Russia’s year-long war with the Ottomans had ended with the signing of the Treaty of Berlin. Consequently, Russia now had sufficient resources to turn her attention once again to Central Asia.

Despite the above changes, Iran and Afghanistan continued to compete for control over the strategically important city of Herat. But more significantly, tensions between Russia and Britain, fuelled by the press on both sides of the conflict, remained. Eventually, both powers concluded that an aggressive policy, rather than diplomacy, was more likely to gain the loyalty of the Central Asian Khanates. As Britain strengthened her hold over Afghanistan and the Sikh territory of the Punjab, Russia either annexed, or brought into her sphere of influence, Tashkent (1865), Samarkand (1868) and Khiva (1873).

Although Afghan policy was to remain neutral in the conflict between Russia and Britain, in July 1878, Russia sent a diplomatic mission to meet with Sher Ali Khan. The envoy was neither invited nor welcome. When the British heard of the Russian presence in Kabul, they insisted that a British mission should also be received by the Emir. Despite the fact that the Emir refused Britain’s request, the Viceroy of India, ordered that a diplomatic mission to Kabul go ahead. However, when the envoys reached the eastern entrance to the Khyber Pass in September 1878, it was turned back by Ali Khan’s men. It was an act that sparked the beginning of the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

In November 1878, a British force of some 50,000 men, mostly Indians, invaded Afghanistan. The first battle took place on the 21st November, at the Ali Masjid Fortress, at the western end of the Khyber Pass. Despite the fact that the British forces were in unfamiliar territory and wearing unsuitable uniforms, their superior munitions won them a resounding victory. Following a further British victory at the Battle of Peiwar Kotal, which is located in today’s Pakistan, Kabul was left virtually undefended.

Faced with total defeat, Sher Ali Khan appealed to the Russians for help. Not wishing to antagonise the British, the Russians advised the Emir to seek terms of surrender. Ali Khan died three months later in the northern Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif. It was therefore left to his son, Mohammad Yaqub Khan, to agree peace terms with the British.

Treaty of Gandamak

On the 26th May 1879, the new Emir signed the Treaty of Gandamak, marking the end of hostilities. Under the terms of the Treaty, Afghanistan ceded territory along her eastern border with British India, including the Khyber Pass, to the British. While the Afghans officially retained sovereignty over the rest of the country, according to the Treaty, they lost control of their foreign policy:

His Highness the Amir will enter into no engagements with Foreign States, and will not take up arms against any Foreign State, except with the concurrence of the British Government. On these conditions the British Government will support the Amir against any foreign aggression with money, arms, or troops, to be employed in whatsoever manner the British Government may judge best for this purpose. Should British troops at any time enter Afghanistan for the purpose of repelling foreign aggression, they will return to their stations in British territory as soon as the object for which they entered has been accomplished.

This clause regarding foreign relations was particularly humiliating for the independent-minded Pashtun tribes. Further provisions allowed for a British mission to be set up in Kabul, increased trade opportunities and the installation of a telegraph line between Kabul and British India.

On the 24th July 1879, a British Mission, led by Pierre Cavagnari, arrived to take up residence in Kabul. Cavagnari was born in Palma. He became a naturalised British citizen and held several important posts with the East India Company. After being a signatory to the Treaty of Gandamak, he was appointed as Britain’s Representative in Kabul. But on the 3rdSeptember, less than two months after his arrival in Kabul, Cavagnari and all members of the Mission were murdered by rebellious soldiers. It was an act that led to the second phase of the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

The small Kabul Field Army, the only British force in the country at the time, was quickly reinforced. By the 8th October, British troops managed to retake Kabul, despite the efforts of a force of 10,000 Afghans to defend the city.

Emir Yaqub Khan was suspected of complicity in the murder of Cavagnari and abdicated. The British were then faced with the question of succession between Yaqub’s brother, Ayub Khan, who was Governor of Herat, or his cousin, Abdur Rahman Khan. Abdur Rahman Khan was chosen and went on to rule for 21 years. In the meantime, Ayub Khan rose in rebellion and on the 27th July after beating the British at the Battle of Maiwand, he went on to besiege Kandahar. Ayub’s victory was short-lived however. The main British forced marched from Kabul and on the 1st September 1879, put down the rebellion at the Battle of Kandahar, so ending the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

Anglo-Russian Agreements

Between the Treaty of Gandamak in 1879 and the Exchange of Notes Between Great Britain and Russia in 1895, there were a number of initiatives and protocols aimed at resolving the conflict between Russia and Britain.

In 1881, as Russian forces came dangerously close to Herat, the two powers set up a joint Anglo-Russian Boundary Commission. Its remit was to define and agree the border between northern Afghanistan and Russia. In September 1885, the Delimitation Protocol Between Great Britain and Russia, was signed in London. This was to be the first of several Protocols aimed at agreeing the border between Russia and Afghanistan.

In November 1893, the British and Afghans agreed the boundary between Afghanistan and British India. Known as the Durand Line, it was named after Mortimer Durand, First Secretary of India. The 800-mile demarcation line cut through the Pashtun and Baloch tribal homelands, leaving ethnic Pashtuns and Balochis on both sides of the border.

Although the Emir of Afghanistan, Abdul Rahman, signed the Agreement, many Afghans have never accepted the boundary, whereas the international community has always recognised the Durand Line as the border, initially between Afghanistan and India, and now between Afghanistan and Pakistan. This is a situation that has contributed to the ongoing instability in Afghanistan. More recently it has proved particularly problematic when tracking down Taliban fighters who are able to cross the border undetected between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

On the 11th March 1895, there was an Exchange of Notes Between Great Britain and Russia that defined the two powers’ spheres of influence in the region. This was ratified on the 10th September 1895 with the signing of the Pamir Boundary Commission protocols. This date is generally recognised as marking the end of the Great Game between Russia and Britain.

*****

(Extract from A History of Central Asia)

Comentários